Cultural collapse

There has been a bit of talk about model collapse, spurred by this Nature paper that was published a few weeks ago. The paper demonstrates some theoretic and empirical results about how training new models from data generated by previous iterations of the model can result in degenerate models.

There’s been a fair amount of criticism of this paper, mainly centering on the fact that the conditions tested in the paper don’t really reflect the way synthetic data is used to train models in the real world.

I’m not particularly worried about the potential of model collapse. There’s lots of active research on how we can make use of synthetic data, and post-filtering seems like a tractable and valid way of avoiding some degenerate cases. What I’ve been thinking about more is a sociotechnical problem: the influx of AI-generated content may not be harmful for training future models, but I worry that the reification of content generated by models that only have the shallowest conception of meaning can result in an ecosystem in which cultural artifacts are slowly leached of any depth. Model collapse doesn’t bother me as much as the potential of cultural collapseMaybe this term is a little hyperbolic, but counterpoint: maybe not? does.

Layers of meaning

Culture is a fuzzy object. I approach culture as socially negotiated meanings of signs. Since I work on language (broadly defined), let’s first consider how this definition plays out in language as a cultural artifact. At the most basic level, we consider words (signs) to have referential meanings. The word “dog” evokes some conception in your mind of the four-legged mammal that wags its tail and barks.

But there are other kinds of meaning as well: there is the social meaning about regional identity embedded when someone, for instance, says “pop” instead of “soda”.https://www.popvssoda.com There is meaning in interaction: it is meaningful to respond to a question with silence, even though no words were ever uttered. And speech is not only referential, but performative. Uttering “I do” can marry a couple; saying “I bet you it will rain tomorrow” initiates the wager (if the interlocutor accepts).These examples are from J. Searle, How to do things with Words. There is even meaning embedded in the way we dressPenelope Eckert, Variation and the Indexical Field and the make-up we apply.Norma Mendoza-Denton, Muy Macha Within all of these semiotic fields, there is structure and meaning.

If there are multiple aspects of meaning, what kind of meaning do language models learn? They are built on the idea of distributional semantics: words take on meaning by how they relate to other words. Food is the set of things that you “eat”. Eating is what you do to “foods”. This relational system of meaning is internally useful for the model, and generally maps on relatively well to how we interpret language, but the meaning making for us happens when we read the tokens that the model outputs. It’s at that point that we decide that “dog” means the same thing to the LLM as it does to you and I.

This is pretty effective in practice, and I find distributional semantics to be a pretty compelling approach to understanding meaning. But it’s worth considering also what aspects of meaning aren’t learned in this scheme. Introductions of distributional semantics often quote computational linguist John FirthFirth, A Synoposis of Linguistic Theory as saying “You shall know a word by the company it keeps.” But in that section, he explains that collocationalA word’s appearance in relation to other words. meaning is but one aspect of meaning, and that collocation should not be mistaken for context, which is sociocultural. Meaning takes place across words, but also all kinds of other signs. Modern systems are learning aspects of meaning that are largely removed from socialcultural context!

What’s concerning is that, for the most part, companies developing AI products are okay with this. At minimum, there is a lack of critical engagement with how language can construct power dynamics and social structure: to build systems that serve a particular language variety means neglecting the diversity of other ones. And this is not just hypothetical. Studies have shown, for example, that speech recognition technology works much worse for Black English speakers than white ones.Koenecke et al., Racial disparities in automated speech recognition

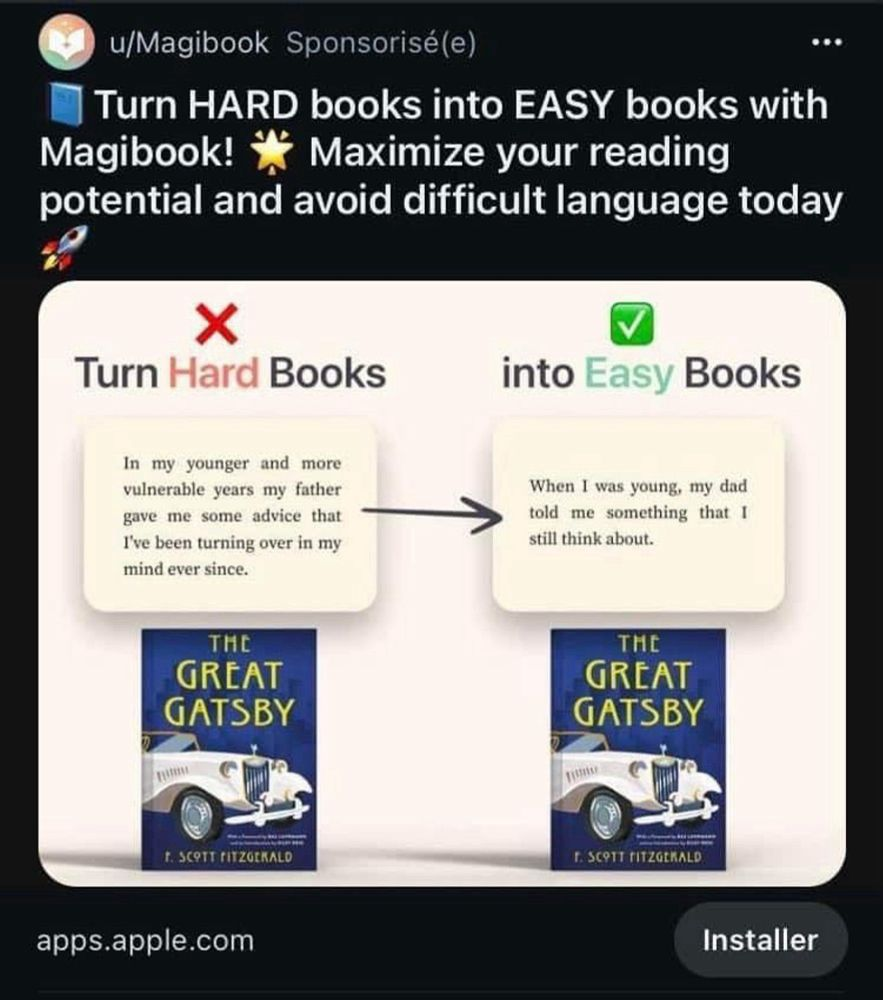

What is perhaps more insidious, I think, is when people build these systems to engage with culture. Like this startup whose ad was floating around the internet a little bit ago:

What bothers me isn’t even the product necessarily; there are instances where simplifying text might be useful! But I object to the problematization of “difficult language”, and especially to the implication that your reading potential is measured by the number of book summaries you can ingest. What aspects of meaning are we losing when we focus solely on the plot? Language is meaningful, and we need to be intentional about which aspects of meaning we keep and which we discard.

This temptation to boil everything down to the essence reflects a total misunderstanding of the point of the exercise in creating and consuming culture. In trying to distill the plot, we may have lost it altogether.

The nature of the enterprise

So what are we trying to do here? Recently, there was an ad for Google Gemini that caught some viewers off guard. A father asks Gemini to write a fan letter on behalf of his daughter.

To many people, myself included, this seems to miss the point of writing a fan letter entirely. But why? Pegah Moradi, a PhD student at the Cornell I-School, wrote an excellent piece about the autopen, the machine that can replicate signatures.Moradi and Levy, “A Fountain Pen Come to Life”: The Anxieties of the Autopen In the essay, she covers three cases in which use of the autopen elides social values that we attach to the act of creating a signature: authenticity, accountability, and care.

That is to say, the shape of the signature doesn’t contain the meaning, but rather what the signature signifies. And this signified meaning comes because we have historically agreed on the cultural significance of a signed name. To mechanically create or recreate the signature outside of that context reduces its meaning. To generate a letter removes the labor of care that gives the letter meaning in the first place. The “grammar” of the fan-mail ritual requires the work that goes into constructing the letter; to remove that work results in a semantically vacuous interaction.

Google’s assertion that generating this letter is equivalent (or preferable, even) to the act of writing one is an erasure of the richness of cultural meaning that gives the ritual of fan-mail its significance. It reifies the idea that culture is reduced to the tokens which comprise the artifact; culture becomes a decontextualized facsimile of itself. This is what I mean by cultural collapse.

In my opinion, the point of writing, of art, of creating and consuming culture, is to create meaning, not to transmit it. I write these words not with the hope that you will think my thoughts, but that they will play a role in inspiring your own.

I don’t mean to suggest that culture and computation are mutually exclusive. My own research is all about computationally studying these other aspects of meaning – for example, what are the different meanings contained in condolence-givingZhou and Jurgens, Condolence and Empathy in Online Communities or embedded in the meme templates that we choose to use on Reddit?Zhou, Jurgens and Bamman, Social Meme-ing In fact, this kind of work has really been enabled by the great progress in NLP and computer vision. But culture as it exists around is incredibly rich with layers and layers of meaning, and we need to think critically about which meanings we are computing on, and which we are ignoring.